It’s a summer re-run. “What kind of Italian cinema fan am I?”

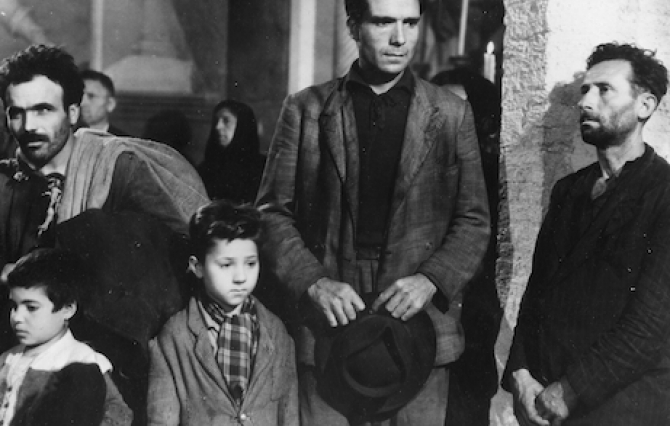

I will never watch De Sica’s Il Ladro di Biciclette again because it made me so ridiculously sad and I couldn’t bear to put myself through that again. His Umberto D. made me want to slit my wrists it’s so depressing. Fellini? I find him a little silly.

I seem like an unlikely candidate for editor of a website called ‘I Love Italian Movies’, I know. I am not particularly in awe of Italy’s Golden Era and I’m not even sentimentally attached to Giuseppe Tornatore’s Cinema Paradiso but I do love Paolo Virzì and Paolo Sorrentino. I love today’s Italian cinema. I believe that a lot of Americans who find it impossible to embrace the current Italian film industry have the same difficulty embracing modern Italy in general. They want Italy to be just like it is in Cinema Paradiso or Il Postino, and they’re disappointed when the stereotypes clash with the reality of modern Italian life.

People read my website and interact with me for a lot of different reasons, and an increasing number of them see what I see and appreciate Italian cinema for what it is, but others bring me their complaints: Italian films are too personal. They’re to “artsy”. They’re not artsy enough. There aren’t enough explosions, car chases, and special effects (young people always say this), they’re getting too “Hollywood”. They’re not Hollywood enough. A few people have told me that they don’t like Italian movies anymore because they aren’t Italian enough.

(Cosa?)

Would Italians make many more movies with car chases and explosions if they had the big budgets to do that? Maybe. Probably. But they don’t. So what do they have? What’s going on in today’s Italian film industry? I’ve spoken with some of my favorite Italian directors and they’ve confirmed what I’d concluded; Italian movie making has changed a good deal in this millennium. There is currently a small army of creative Italian actors and directors who are putting themselves out there, trying new things, and producing innovative work; but is anybody paying attention?

Daniele Luchetti’s latest film, Anni Felici or Those Happy Years is a story based on his childhood and his truly “out there” parents. The memories of his parents, his childhood, and how they’ve affected him as a grownup are both heartbreaking and funny, and Luchetti says that it took jumping into “acqua fredda” (cold water) and just doing it, that is to say, telling the truth about his life.

He talked to me about shooting the film and how everyone kept telling him how brave he was for talking about his artistic, eccentric family and their volatile family dynamics and that he really didn’t understand what they were saying until he started the editing process. Then, and only then, did he start to see what others were seeing. He found that it had touched something in him and was unable to leave the editing room. He spent a full year there with his collection of stories that has says either had actually happened, he’d been afraid would happen, or he would have wanted to have happened.

I told Luchetti that I saw him as a very modern Italian director who seems to want to break away from the old school directors. I pointed to one particularly emotionally painful scene in which the lead actress, Micaela Ramazzotti, has a confrontation with her son and then a complete meltdown at the beach, and I marveled at his ability to pull that kind of performance from actors in all of his movies.

Micaela Ramazzotti is a wonderful actress, but I have never seen her like this. How did Luchetti get this kind of performance out of her?

He said that beginning his career he had wanted to make classic films, but as he grew as a director his methods changed and he saw the importance of the director/actor relationship. He said that in the old days, Italian director had an almost antagonistic relationship with the stars, but that he was much more interested in the actor and what they embodied as human beings. Allowing the actor to contribute to the interpretation of the character has given a dimension to performances that just wasn’t there in movies from Italy’s golden era.

I wondered if Luchetti’s mother, who is still living, minded very much that he’d so openly exposed her personal life, specifically her sexuality, and he admitted that she’d worried about what the neighbors were thinking, but not for the reason one might guess. “She was mostly worried about the meltdown at the beach scene, and the anger that the boy showed to his mother”.

I recently spoke with director Francesco Munzi about his latest filmAnime Nere, Black Souls – and if you have the opportunity to see it please do! You can check my website – I Love Italian Movies – for cities and dates.

Anyway, Munzi admits that he wants to distance himself from the filmmakers of the last 30 years. And he has. Francesco Munzi is one of those directors that I am most interested in these days. Italian movies have never been better because of ones like him who, as he says, “speak of our reality, take risks, and want to invent something new.”

I asked him what he thinks he is doing that is different from the old directors, and he was much too modest, claiming that he’s not alone, but part of a group of filmmakers who look to their grandfathers, and not their fathers, for inspiration,trying to create something that is “somewhere between our grandfathers and the future.”

Probably my favorite interview was with Italian director Roberto Andò about his thoroughly entertaining political comedy, Viva La Libertà. Viva La Libertà is the story of the Secretary of Italy’s leading political party, one in big trouble and with plummeting approval ratings. When things are at their worst, the secretary, played by Toni Servillo, flees in the middle of the night to an old girlfriend’s house in France, leaving his closest aide scrambling to deal with explanations for his absence. Instead of admitting that he can’t find his boss, he enlists the Secretary’s twin brother, also played by Servillo, to fill in for him. Andò based the movie on his own award-winning and best-selling book, ‘Il Trono Vuoto’ (The empty throne).

I told Andò that I thought of him as part of that new wave of Italian directors, ones that were changing the face of Italian cinema, and he welcomed that perspective. He talked about what he called a “mortification” of Italian cinema that had developed, where, unlike in the US where filmmaking is a strategic industry, Italians just wanted movies that “didn’t hurt”. He told me a great story about Bernardo Bertolucci, who, Andò said, for years made beautiful films that nobody saw. “It was in the moment that Bertolucci decided that he wanted an audience that he began to fill theaters”, he continued, “because if you don’t want an audience, then why would an audience want you?” “In the last ten years”, he said, “filmmakers have given up on the idea of making films with no relationship to the audience.”

As far as I’m concerned, I don’t expect Italians to crush grapes with their feet to the tune of the Tarantella any more than I expect them feel compelled to compete with the ghosts of “Golden Era” of Italian Cinema. More than anything, I just want to be entertained, and I find contemporary Italian cinema entertaining. “The golden age is before us, not behind us”. Shakespeare said that, not me, and I’m not sure if it’s true for everything, but it is for Italian cinema.