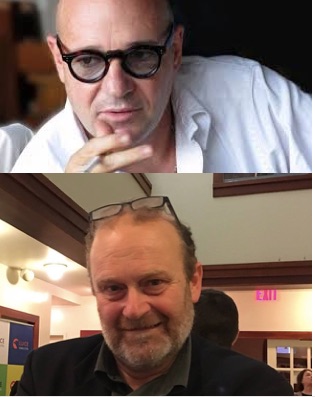

Gianfranco Pannone and Gianfranco Rosi, the quest for documentary in its purest form, and the trouble with Michael Moore.

I got to meet and talk with these two Italian directors who presented films at the past two Venice Film Festivals and they taught me some important lessons about documentary filmmaking; it doesn’t have to be shocking. It doesn’t have to accuse anybody of anything. It can be kind, and it can be a celebration rather than an indictment of humanity.

Last year director Gianfranco Pannone brought his L’Esercito Più Piccolo Del Mondo, a skillfully and sweetly told story of young men in today’s Vatican Swiss Guards, exemplary young men who have just arrived at Vatican City for their training, sincere and ready to work hard.

Gianfranco Pannone prefers “a kind of documentary that questions, that believes in an active participant, that provokes.”

“I like to plant doubt”,he told me, “and that’s what (Michael) Moore doesn’t do. What he says in his films often are things that I agree with, but I don’t like his way of taking the viewer by the hand, as if he were a child. Ultimately you don’t go to see a Michael Moore film to discover anything new, but to have something confirmed, and I this is what I don’t like. I have great respect for Moore, but I think more about film that is less “state sponsored”, that believes in something very important and is one that expresses a thought. I prefer cinema of style, that knows how to take the audience using the language creatively rather than expressing itself with the words, words that can very easily become slogans.”

Two years ago Gianfranco Rosi won the Golden Lion at Venice with his film Sacro GRA, about the Grande Raccordo Anulare, the giant ring of a highway that circles Rome and the people who live out there. He spent about two years living with them, finding out who they are, and filming them.

In snippets, we see the lives of an EMS worker, a scientist studying the area’s palm trees, strippers, and a kitschy couple and their kitschy house that gets rented out for parties and for movie sets. The clear favorite of the director and Venice Film Festival audience were Paolo and Amelia, father and daughter, sharing a tiny apartment and watching the world of the GRA philosophically from their window.

Rosi showed me what he saw in them, “the generosity of sharing their lives with the world”, he said. “Each of them was a potential for a whole film”.

And what does Rosi say when asked what it was that they had to do with each other? If they had a common thread? “Of course they do”. he said, “I found seven people who don’t complain about life. They are all very open, and all use a very poetic language.”

It’s been said, and Rosi confirms it, that the Venice Jury, headed by Bernardo Bertolucci, voted for Sacro GRA unanimously, and that no other nominated film was seriously considered. Rosi told me that Bertolucci had said that he loved it because “it was a film with no judgement”, a trait Rosi feels has become too rare in documentaries, particularly American ones, like Michael Moore’s.

“I don’t like this kind of filmmaking”, he said. “Everybody wants to be a small Michael Moore. I like to capture positive elements of the world.”

And though some may say that Rosi has a talent for finding interesting people, I’d say he his talent is finding the interesting thing in all people. It seems unfair to call the people in Rosi’s Sacro GRA “ordinary”, but in truth, they are. We’re all ordinary and fascinating, each in our own way, and Gianfranco Rosi has made his living pointing that out to us.

Gianfranco Pannone takes it even a step farther when he talks about what he wants audiences to get from his work: “I’d like audiences to take an urgent need for humanity, the same humanity that Pope Francis passed on to me in the months that I was filming, I believe that today there is a great need to pass on to others the power of humanity to those who need empathy, attention, and someone to hear them. And those that have seen it (the film) I think have recognized the human force that my film follows in the 80 minutes of the story. From the beginning, the idea of L’esercito…it was to give to the world a group of young men that are like so many others, but have decided to serve the church in 16th century clothes. A curious and confusing thing. Did I succeed? It’s not for me to say, but to me, the public seemed curious to know. Certainly this film gave me so much in human terms. It was a real honor to be able to be able to achieve it and to bring it to movie theaters.”